Article by Carola Capello

Translated by Simona Sucato

“As a child, my parents taught me to say Inch’Allah (God willing) when I plan to do something. Here, Kufid is this: planning something unplanned. An oxymoron”. As Elia Moutamid states – Moroccan director, special mention as best new director at 2018 Nastri d’Argento –, whose first film Talien won in 2017 the Gran Premio della Giuria at Torino Film Festival.

The director immediately shows to the spectator what is Kufid: an unplanned film, or even better, an unexpected film. It is in fact his voice that, in the opening, tells he had a completely different intention for his second feature film compared to the one he then realized.The idea was to shoot a documentary on the relationship between man and urban planning in Medina, Moutamid’s birthplace. The gentrification’s theme should have been central, telling of human dynamics through autobiographical narration but, once the inspection is over and he goes back to Italy, something unexpected is unleashed in the community, kufid precisely. The disruption of the plans caused by pandemic and the forced quarantine, however, are a valuable oppurtunity for the author to reflect.

The documentary, set in Brescia, Lombardy, one of the areas most affected by virus, alternates video footage shot inside of Moutamid’s house – cleaning, gardening and video calling – with images of deserted streets and buildings that appear abandoned. The intention is not to make a film about the pandemic, but to make a film during the pandemic: a period to make the forced isolation fruitful by stimulating the mind and creativity.

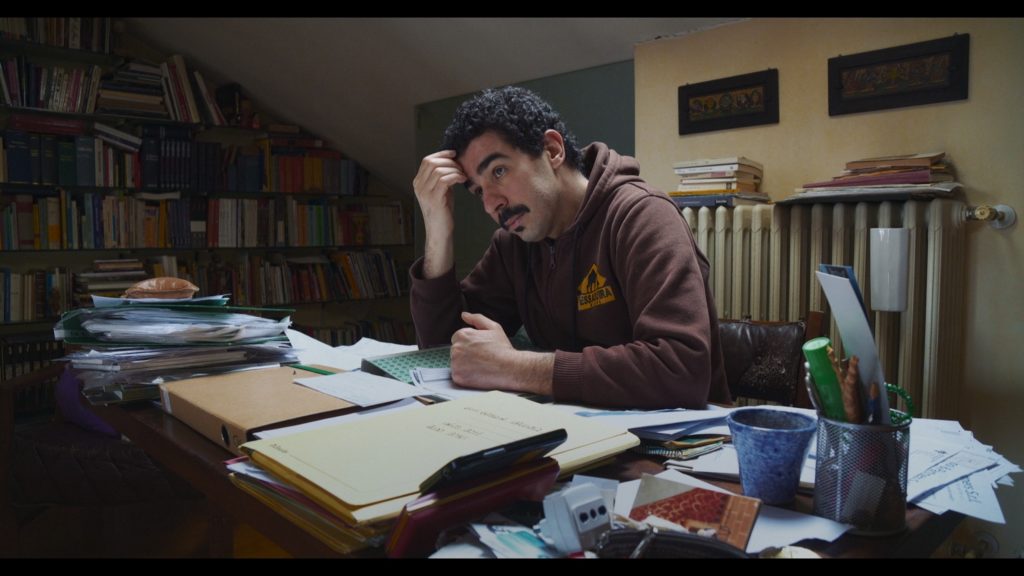

The aim seems to be to narrate the outside world from within house’s walls but the real goal for Elia Moutamid –that for this occasion has taken care of, in addition, also writing, photography and editing –, is to build a film about himself, of which to be actor and narrator. Indeed, the director tells the story of his identity divided between Morocco, his homeland, and Lombardy, the Italian region in which he grew up.And it does so also through the languages: Arabic, which can be called Moutamid’s “Language of the head”, passing through Italian to the Brescian dialect, such as “languages of the belly”. His own story, of personal convictions and contradictions, is therefore successful thanks to the continuous “cultural exchange” between these two countries (made explicit by the images and the linguistic register) and the constant passage between the external world and the most intimate and profound, made of emotion, reflection, but also of concern, of one’s own interiority.