Article by Carola Capello

Translated by Giulia Neirone

After Aquarela – cautionary film about water strength and beauty premiered in 2018 Venice Film Festival and included in the 2019 documentary nomination of the Academy Awards – Gunda is another simple, although not granted, food for thought by the Russian director Victor Kossakovsky. Set in a farm where we can only see a wooden house surrounded by nature, the main character is a group of animals in their everyday life.

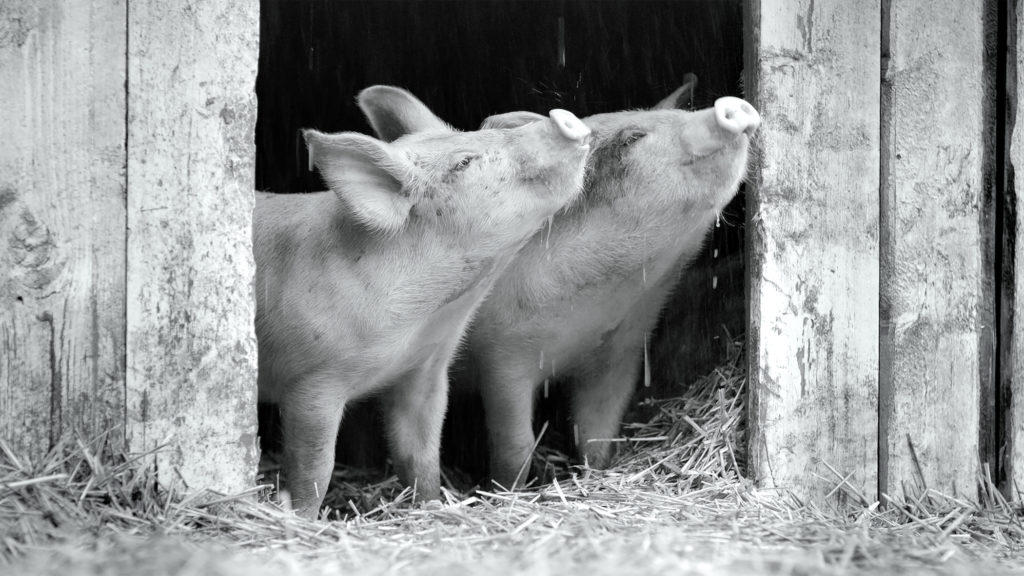

Some cows graze in a field, birds suspiciously explore the bush and Gunda, a sow, gives birth to her piggies. The film doesn’t have a proper plot, there are neither dialogues nor music nor captions. There are no actors that give us information about what we are watching. Nevertheless, a few minutes into the film, what might seem a simple documentary about the delivery of a sow, turns out to be an extraordinary tale.

As they were stars, animals are pictured through expressive and tender close ups, thanks to an incredible photography. Slow and silent tracking shots follow them closely, giving us vivid images, new yet timeless, sophisticated yet simple. The director has the ability to make creatures and events compelling and to use nature sounds carefully. In this way, he creates an engaging atmosphere and a significant emotional tension. These elements enable the viewer to listen to the animals and overcome species boundaries by investigating the mystery of their conscience.

In its essentiality, the documentary seems to be a tribute to the early days of cinema. The film was shot without a script and in black and white, in order to demolish every human narration perspective. Thus, the viewer is able to completely focus on the main characters’ “soul”, rather than on their looks. Victor Kossakovsky builds a genuine image, which represents an invitation to understand the essence of cinema. That is to say, observing the reality as it is, without deception and tricks, and drown your own conclusions. Since Kossakovsky ironically stated to be the first vegan in the Soviet Union, the film can be read as vegan propaganda. The director leads the viewer towards a rough realization which encourages to think about the similarity between humans and animals, destroying the presumption that men are the only one that have feelings and conscience.