Article by Andrea Bruno

Translated by Nadia Tordera

Divided into two separate programs of about one hour each, there are eight films that make up the competitive ITALIANA.CORTI section of the 38th Torino Film Festival. The variety of gazes is remarkable but perhaps there is a common thread that unites them and that must be sought in the attention that almost all directors turn to intimate and everyday stories, often able to rise, sometimes unexpectedly, towards the territories of epic. Above all they share a lively linguistic research which usually uses archival material, found footage, Super 8, or collage in the almost desperate experimentation of new expressive solutions.

ALL’ALDILA’DIQUA (30’), the longest of the selected titles and the most ambitious in the aims from which it starts, well exemplifies this set of tensions. The director Alessandra Cianelli embarks on a research journey into the Italian colonial past starting with the discovery of some letters from her grandfather. The images of the present-day Naples flow on the screen together with those of the past indissolubly linked by a single cross-fade. On the other side of the spectrum there is the very brief NON CE NE SIAMO RESI CONTO by Giorgio Vicozzi and Alfredo Dante Vallesi, a three-minute dada flash which illustrates didactically some Pasolini’s thrusts to society consumerism through the animation of prints and newspaper clippings.

Among the most successful titles there is LA TECNICA by Clemente De Muro and Davide Mantegna, the only short film of the section to explicitly measure itself with classic narration (even if giving space to various cinéma vérité impressions). In the chronicle of Leo and Cesare’s summer, the archetypes of the bildungsroman and arcadia appear, and the two directors are very good at modeling this material in a small space (just 10 minutes) thanks to an excellent use of decoupage. ISSA (12’) is similar to it in aesthetics and pastoral tones, set in a small village in the Sardinian countryside destined for depopulation. But in this case the narrative and its paradigms (here we are struggling with pregnancy and childbirth) are filtered through the lens of symbolism.

OLD CHILD (16’) by Elettra Bisogno is remarkable because it knows how to reach poetry with discretion. Hazem, who clandestinely left Palestine to arrive in Europe, tells his story whispering from the off-screen, while confused fragments flow on the screen that make up a real stream of consciousness in images. The finale set in the seaside, made of shades of blue and pure light, reinforces the references to Joyce and the Homeric Odyssey.

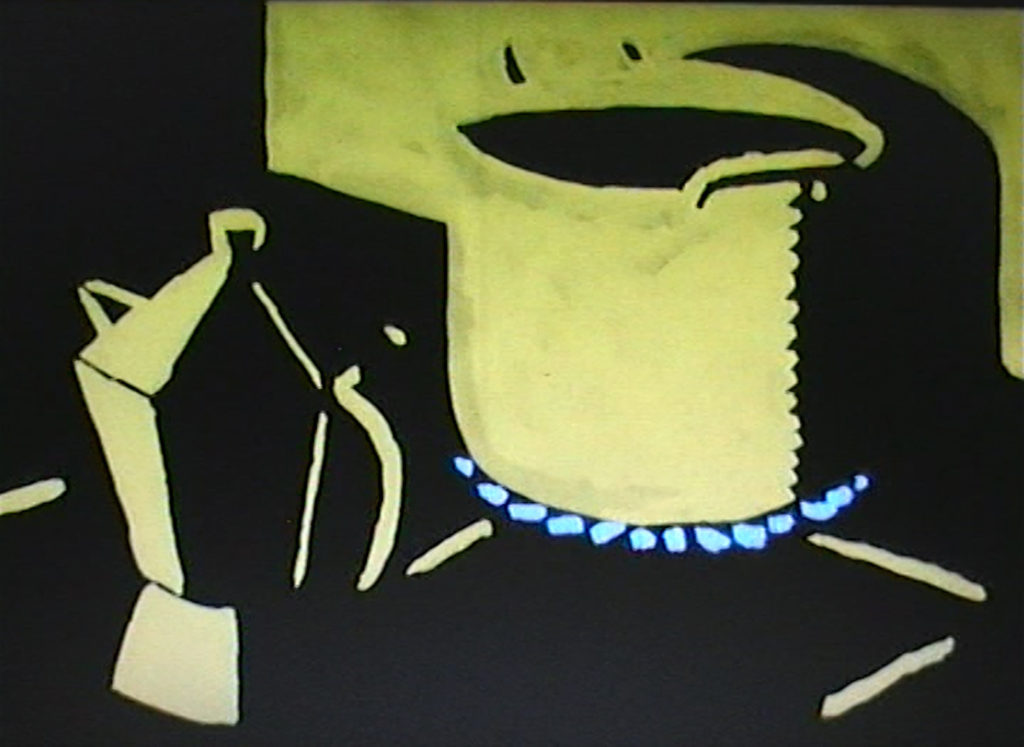

MALUMORE (12’) by Loris Giuseppe Nese is instead concrete music. The ticking of a clock, the rattle of an elderly man dying, the fragments of the mass or a soap opera that come from the television turned on, joined by the electronics of Davide Maresca, tell the routine of anxiety in a popular neighborhood of Salerno. Everything is put into images with suggestive animation made up of silhouettes, shadows and chiaroscuro. Even ‘NA COSA SOLA (24’) revolves around a waiting bell – the one you breathe in the stations of a railway line at the foot of Vesuvius – but the path chosen by the director Giovanni Sorrentino is that of the documentary.

The music also appears in SRISARAYA (11’) by Patricia Boillat and Elena Gugliuzza. The very sober comment is by Giovanni Venosta, a fellow composer of Silvio Soldini, but to see the houses of Thai spirits on the side of the streets, one in line to the other, we have to think about Philip Glass and his rhythmic. With a beautiful transition from the huge to the small, the two directors create a parallelism between these small sanctuaries and the reality now almost vanished of the independent cinemas of Southeast Asia.

Finally, to these eight titles is added an appendix out of competition – THEEND (6’) – signed by Jacopo Benassi, who between Vincent Price, Creature from the Black Lagoon and Lydia Lunch, composes an elegy for the death of underground art.