Article by Cristian Cerruti

Translated by Francesca Luna Lombardo

“Why can’t a woman be named Luciano?”

Lucy Salani

C’è un soffio di vita soltanto, presented in the section “Fuori concorso / L’incanto del reale”, tells the story of Luciano Salani, the oldest living transsexual in Italy, whose existence was marked by survival in the Dachau concentration camp. Starting from the idea of making a documentary on the story of a survivor, Botrugno and Coluccini find themselves faced with a character who goes far beyond any possible categorisation. Lucy is fluid, multifaceted, alien. A fluidity that emerges right from her choice to keep her first name: Luciano. The proposal to officially change her name to a feminine one, made several times to Lucy, has always received a negative answer. The name is not seen as a label to define her gender, but represents the memory of her parents, a memory that forges Lucy Salani’s personality.

C’è un soffio di vita soltanto begins with the footage of an eclipse and, after interweaving the story of Lucy’s life with almost sci-fi imagery, ends with Kubrick’s image of the first developments of a foetus, almost as if to represent the palingenesis of a new world. If a new world is needed to create a God who would not allow what has happened, Lucy’s memory shows us that, first of all, a new humanity is needed, probably one alien to the previous one.

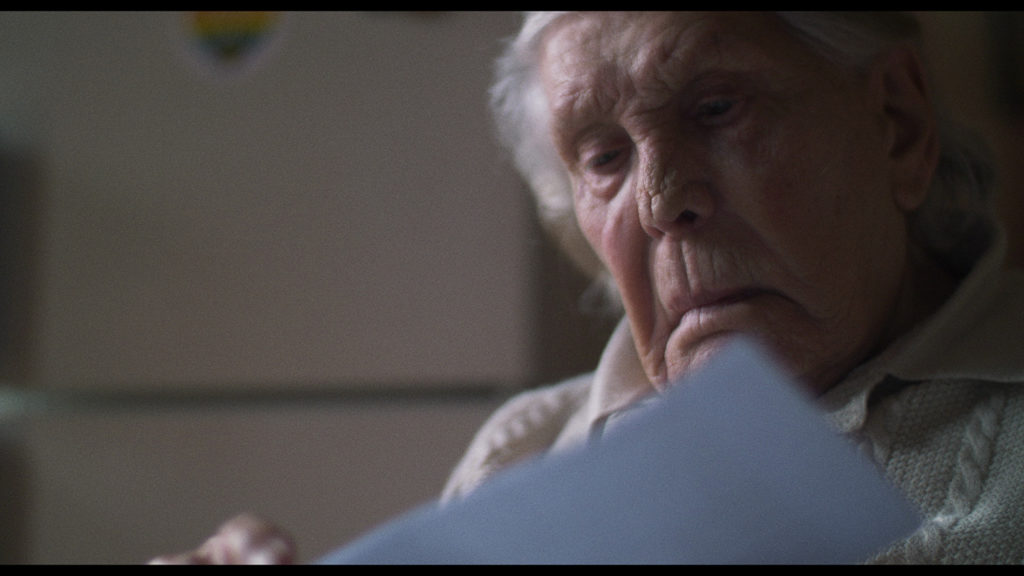

And it is precisely in the memory that the 96-year-old Lucy materialises. To tell her story, the two directors rely on the dialogues between Lucy and the visitors to her house, which becomes the film’s gravitational epicentre. The protagonist implements a policy of welcoming the alien, making her home an intersection of different cultures and histories which, by interacting with Lucy’s, bring out her memory. The people in the old woman’s life are also alien figures, estranged in some way from society: her transsexual friend, the Muslim boy welcomed into her home, the orphan girl adopted many years before, with whom she has created a familial bond that persists even after her departure. It is the filmmakers themselves who are welcomed by and attracted to Lucy: in the narrowness of the domestic spaces, the camera remains constantly focused on the protagonist, carrying out a daily monitoring that consists of intimate and private moments that show another side of C’è un soffio di vita soltanto: the film is also a delicate tale about old age.

Lucy’s story is, however, marked by her internment in the Dachau concentration camp. What is surprising is how the protagonist is able to seize the memory of those terrible events by transforming them into an instrument of strong self-determination. The attendance to the celebration of the seventy-five years since the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp becomes the aim of Lucy’s life and it is the film itself that strives towards this moment. While most of the story is told through very close-up images, the arrival in the Martian territory of the Dachau concentration camp marks a directorial turning point with long shots taking over. Images that seem to come from another planet, but which in fact frame the theatre of one of the saddest chapters in human history. In this foreign territory, Lucy stares at a large cross. At this point, the camera returns to focus on the protagonist:

“If there really were a God, all these things would never have happened. But unfortunately there isn’t. God is us, because it is our will that commands the world, not God. What God? Fortunately,I got to the end, at least I could see that it was not worth staying on this planet”.