Con Lonely Seventeen, nel 1967 Pai Ching-jui realizzava un’opera manifesto: un affresco dell’adolescenza e delle sue problematiche, all’interno di un contesto culturale e sociale problematico per via della censura e del controllo statale. A oltre cinquant’anni di distanza, Lonely Seventeen – un titolo di per sé evocativo — offre ancora un racconto fortemente attuale nel ridestare sentimenti e sensazioni assopiti da tempo.

Continua la lettura di “LONELY SEVENTEEN” DI PAI CHING-JUIArchivi tag: RETROSPETTIVA

MEZZOGIORNO DI FUOCO – RETROSPETTIVA SU JOHN WAYNE

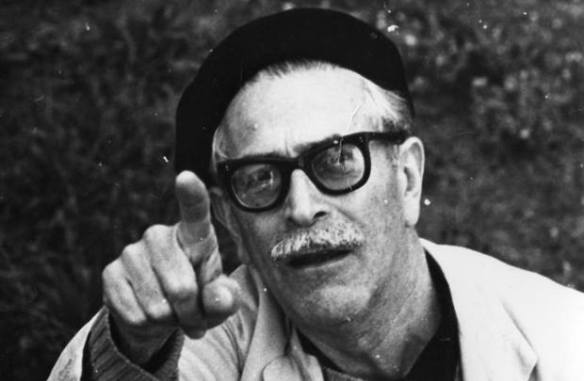

Lo studioso Yves Kovacs individuava in John Wayne la quint’essenza della Hollywood classica. Un attore che in ogni ruolo riflette una componente monolitica, burbera e un po’ disillusa, ma anche un’aura mitica che, nel corso degli anni, ha reso Wayne il simbolo del cinema americano. I personaggi interpretati da Duke si eclissano dietro il suo sguardo glaciale e il perentorio tono di voce capace di mettere fine a qualsiasi discussione; ma soprattutto invecchiano assieme a lui, si confondono con la sua vita fino ad alterarne l’identità. Sarà proprio l’attore ad ammettere che in ogni film il suo ruolo è quello di interpretare John Wayne, senza curarsi troppo del personaggio. La sua immagine si è costruita sulla ripetizione dei codici di un unico genere e pensare a John Wayne oggi vuol dire pensare al cinema Western stesso.

Leggi tutto: MEZZOGIORNO DI FUOCO – RETROSPETTIVA SU JOHN WAYNELa seconda (e ultima) edizione del Torino Film Festival non poteva che concludersi con una retrospettiva su John Wayne, attore molto amato dal direttore Della Casa che ha deciso di riproporre in sala alcuni dei titoli più apprezzati nella sua infinita carriera. In ordine cronologico troviamo il capolavoro di Raul Walsh Il grande sentiero (The Big Trail) del 1930: il primo ruolo importante della carriera di Wayne, ma anche grande flop al botteghino che relegherà il genere western alle produzioni di serie B prima di essere “salvato” da John Ford con Ombre Rosse (Stagecoach, 1939). Successivamente troviamo Il fiume rosso (Red River, 1948), uno degli splendidi western girati dalla volpe di Hollywood Howard Hawks. Sarebbe scontato elencare i temi, ormai codificati, che si possono ritrovare nel repertorio hawksiano come l’amicizia virile che sfocia in una velata omosessualità, la morale della tenacia e della dignità. Per apprezzare Il fiume rosso basterebbe soffermarsi su una delle più belle panoramiche della storia del cinema, in cui Wayne scruta la vallata per poi esclamare «take’em to Missouri Matt!».

In una retrospettiva su Wayne non può naturalmente fare a meno di John Ford, il padre del cinema Western e grande amico dell’attore: il TFF porta sugli schermi due film del maestro, I cavalieri del Nord Ovest (She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, 1949) e I tre della Croce del Sud (Donovan’s Reef, 1963). Il primo fa parte della trilogia sulla cavalleria statunitense, mentre il secondo è un’opera piuttosto sconosciuta del repertorio di Wayne e di Ford, realizzata – si dice – come pretesto per una vacanza nei mari del Sud. In seguito, troviamo Hondo di John Farrow del 1953, ispirato a un racconto dello scrittore Louis L’Amour ed esordio sul grande schermo di Geraldine Page; una divertente commedia di Henry Hathaway, Pugni pupe e pepite (North to Alaska, 1960) dove Wayne dà il meglio di sé come attore comico tra i ghiacci dell’Alaska; e infine l’ultima fatica dell’attore, ovvero il western crepuscolare di Don Siegel, Il pistolero (The Shootist, 1976).

Sospeso tra tradizione e ironia, il film di Siegel si apre con un omaggio (quasi elegiaco) all’attore, con una carrellata di scene dei vecchi film interpretati da Wayne, montate ad hoc per sottolineare le abilità da pistolero del suo personaggio J.B. Books. Un film che si misura dunque con la storia del cinema ma anche con la realtà dal momento che tutto il film ruota attorno al tumore di Books, la stessa malattia che colpisce Wayne in quegli anni. Il pistolero e l’attore sono prossimi alla fine, e non c’è un addio più consono se non una sparatoria in un saloon (tutta girata in campi lunghi) dove Wayne riscrive il suo destino, “aggiustando” la realtà attraverso la finzione e regalandosi un’uscita di scena maestosa, degna del suo personaggio: nel finale non si lascia vincere dalla malattia, ma viene ucciso con un colpo di pistola.

Luca Giardino

CARLOS VERMUT

Finalmente Carlos Vermut è arrivato in Italia. A porre fine alla colpevole miopia nei confronti del suo cinema, riservatagli dalla distribuzione e dai festival italiani, ci ha pensato il Torino Film Festival. Fiore all’occhiello di questa quarantesima edizione, la personale dedicatagli conferma la grande capacità del festival torinese di far scoprire al pubblico italiano cineasti pressoché sconosciuti ma sicuramente meritevoli di mostrare il proprio lavoro a una platea più ampia possibile. Nel caso del cinema del giovane regista spagnolo vale anche l’opposto: non solo egli è sicuramente degno di essere scoperto, ma il pubblico stesso merita di assaporare le sue opere, in quanto rari esempi, nel panorama odierno, di film capaci di coinvolgere gli spettatori, senza però trascurare uno studio attento e approfondito della società odierna.

Continua la lettura di CARLOS VERMUTJOANNA HADJITHOMAS E KHALIL JOREIGE

Article by Elio Sacchi

Translated by Federica Maria Briglia and Mattia Prelle

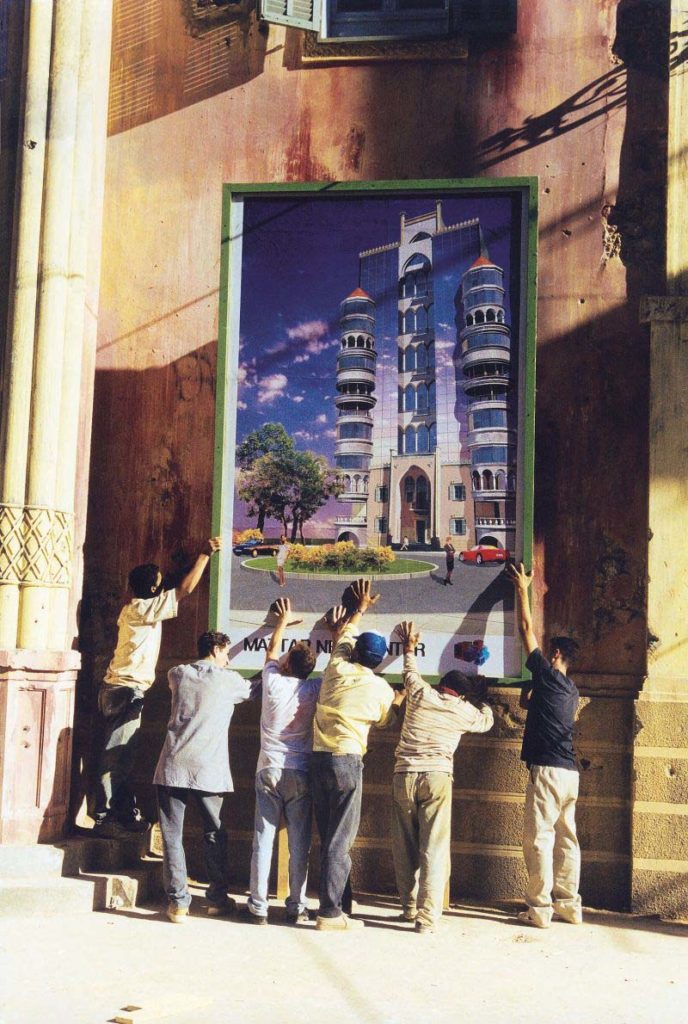

The cinema of Joanna Hadjithomas and Kalil Joreige – to whom the thirty-ninth edition of the Turin Film Festival dedicated a solo show and a masterclass, both curated by Massimo Causo – may lie between the beginning and the end of their artistic and cinematographic career. That means it is between the postcards of the opening credits of their first feature film, Around the Pink House (Al Bayt Al Zaher, 1999), and the box, the audiovisual archive of memory and remembrance that, like a very personal and foreign body, opens Memory Box (2021). Between these two extremes, within the more general framework of the history of Lebanon, of its destruction and of its reconstruction, there is a long and complex reflection on cinema, on the status of the image and, in particular, of the memory-image. When the past passes, the construction of a collective and shared memory becomes a difficult operation, which leaves enough room for memories and handy images that preclude the possibility of a complex narrative in favour of a superficial, conciliatory and pacifying narrative. This is what often happens after internal or fratricidal wars, which are followed by a reconstruction so fast that the past cannot be processed. This is also the case of Lebanon, considered the Switzerland of the Middle East in the 1960s: it was turned upside down first by a civil war and then by the conflict with Israel. The whole artistic parable of Hadjithomas and Joreige refers to this reality, and, in addition to cinema, crosses over into photography, performance arts and plastic arts. Their artistic parable contains its own moment of reflection and self-reflection. It is particularly evident in the performance Aida Sauve Moi, which makes explicit the questions that drive the expressive and creative urgency and necessity of the two directors: this is an indefinite and permeable border between reality and fiction, between personal experience and history. Their parable also contains the concept of latency, which is not only the physical, chemical and material concept of the negative impressed and never developed, but it also represents all the individual and particular latent stories, existing and never revealed, of the kidnapped and murdered Lebanese citizens, and of all the corpses that have never been found. Other elements included in their artistic parable include: the materiality of the image and of the testimonial object itself; the crossing and the attempt to take back public and collective spaces; and, finally, a boundless love for cinema. The last of these elements should be interpreted above all as an instrument of resistance and political commitment (in this regard, see Open the Door, Please [2006], a passionate and cinephile homage to the cinema of Jacques Tati). Joanna Hadjithomas and Kalil Joreige’s one is a self-reflexive cinema that also reflects on the status of the images it represents. This cinema has its genesis precisely in the overexposure to stereotyped images, whether they concern the civil war or the 1960s, as witnessed during the masterclass entitled Memory Work – Resistant Aesthetics in Hadjithomas & Joreige’s works (Rosita Di Peri also attended the event).

Actually, Around the Pink House has its origin in an earlier photographic project called Wonder Beirut. Hadjitomas and Joreige invented the figure of a Lebanese photographer, who immortalised Beirut in the 1960s and 1970s, before the civil war; the photographer then literally and materially burnt the buildings depicted on his postcards as they were bombed until the images were completely transfigured. The film does not tell the story of the Lebanese civil war, but rather the reconstruction of the capital in the 1990s, a period in which “the sound of bombs has given way to that of bulldozers” and in which the rubble shown in the background, physical and painful traces of a recent past, enters into a profound dialectic with the story of reconstruction and rebirth, which nonetheless involves the destruction of entire buildings. The maison rose itself is an archive of memory, of Lebanon’s history, a physical place that bears the marks of war, the memories of people who disappeared and the presence of refugees who were forced to leave their villages.

The maison rose is also an attempt done by a community to take its space back. This is the same public and collective space that Catherine Deneuve, the spirit of European cinema invoked in Lebanon as a foreign and empathetic body and led by Rabih Mrué (a recurring actor in the filmography of Hadjithomas and Joreige, he is a face that embodies the generational drama), wants to see but is prevented from doing so.

Je veux voir (2008) is a journey through a country devastated by the conflict with Israel. It stems from the need to show unconventional images (i.e. different from those broadcast by the various television stations) and to investigate new places, in a sort of palingenesis of the gaze and images of war. While in Rounds (2001), the wandering around the city – a Beirut that uses the rubble of buildings to build new roads by the sea – programmatically precludes the vision of public and city space, which is relegated to an off-screen that is always overexposed. Kiam 2000 – 2007, which began in 1999 and ended in 2008, is also the ideal counter-field to Je veux voir, since the detention camp described in it is an absolute off-screen narration, which can be only imagined by the human testimonies of the internees who invite us to reconstruct it in absentia. The film opens, once again, to an explicit reflection on memory. In 2006, in fact, the camp was turned into a museum and, still in 2006, was bombed by the Israeli army. Made almost entirely with rigorous close-ups and extreme close-ups, these vicissitudes gave rise to the need for Kiam: the urgency of the testimony necessarily refers to the camp, to its presence, it summons it and ultimately affirms its existence.

Their cinema is constantly in communication with the absence and the missing pictures, both personal, as in The Lost Film (Al Film Al Mafkoud, 2003), and collective (The Lebanese Rocket Society, 2012). And the ghost – as the directors admitted more than once – is a recurring figure in Lebanese culture and in its people’s daily life. A Perfect Day (Yawmoun Akhar, 2005) deals with ghost stories: piled up corpses in mass graves that no one discovered during the reconstruction of Beirut liven up and expand the story, claiming through a deafening silence their existence and death. This is a matter of faith and persistence of memory, because who believes in the ghost’s survival will be able to see it and reunite with it, whereas who tries to forget is forced to roam along the streets of a city that cannot be owned and cannot be seen (the contact lens do not adjust the sight, they rather produce a twisted and hallucinated vision of Beirut). Moreover, the film is based on the story of Joreige’s uncle, kidnapped during the war and still “missing”; one day, after many years, the directors found an undeveloped photo negative, a latent and phantasmal picture. The decision of transforming the negative-in-power into image-in-act corresponds to the desire of bringing back to light a unique and universal story, both personal and collective, through different concrete manipulations of the film. This story carries the marks of history, of the flow of time. Similarly, the city of Smirne is, in its reconstruction, a physical trace of the history passage: in Ysmirna (2016) the comparison between the early 1900s city map and the modern one shows the temporal distance of a mythical city, told by Joanna’s family and the one of the poet Etel Adnan (both of them have never been in the city of, respectively, their grandparents and parents), through an oral storytelling that intends to be a reenactment of a past in which one can find their roots.

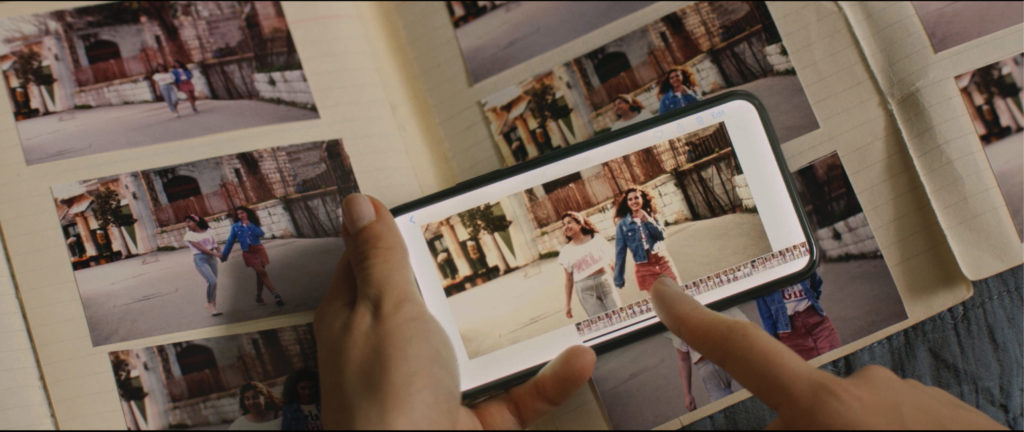

Hadjithomas and Joreige’s more than twenty years of artistic activities and personal experiences break into a Lebanese family migrated to Canada, in the form of a big cardboard box. The package from Lebanon is an archive containing letters, photographs, notebooks, recordings of radio broadcastings and undeveloped films (Memory Box is freely inspired by the mailing correspondence that Joanna had with a friend of hers who migrated to Paris, suddenly interrupted after six years). This is an archive that causes the explosion of the underlying conflicts between the three different generations and, at the same time, it’s responsible for the deflagration of the film. Even if most of the films by Hadjithomas and Joreige have a material essence (and most of the films shown during the retrospective were projected in 35mm), Memory Box has a digital concept. Alex, the daughter, edits and manipulates the civil war testimonies according to her own grammar, which includes smartphones, instant communication, digital post-production and immateriality. The distance in space and time, and the reconstruction of the 1980s through their icons are not nostalgic at all, they are just needed to testimony and transfer the story. The intergenerational confrontation (the grandmother, Maia; the mother, who represents the directors’ generation; and the daughter) is about approaching the story of Lebanon, and thus becomes a matter of identity and belonging, that is opening up several possibilities of the storytelling for those generations that never experienced the conflict and whose memory may be lost.

The one of Joanna Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige is an artistically and conceptually coherent career that finds its raison d’être in the moral duty of making concretely, materially and visibly collective and public what the passage of the story of Lebanon has discolored, as if the past were an unimpressed and undeveloped film. An idea of political and civic cinema, a product of more than twenty years of activity that displays in the intergenerational confrontation of Memory Box the need to narrate the past in order to live the present and to imagine the future once again.

JOANNA HADJITHOMAS e KHALIL JOREIGE

Il cinema di Joanna Hadjithomas e Kalil Joreige – a cui la trentanovesima edizione del Torino Film Festival dedica una personale e una masterclass entrambe curate da Massimo Causo – può essere compreso tra l’inizio e la fine del loro percorso artistico e cinematografico, ovvero tra le cartoline dei titoli di testa del loro primo lungometraggio, Around the Pink House (Al Bayt Al Zaher, 1999), e la scatola, archivio audio-visivo del ricordo e della memoria che, corpo estraneo e così personale, apre Memory Box (2021). Tra questi due estremi, all’interno della cornice più generale della storia del Libano, della sua distruzione e della sua ricostruzione, si apre una lunga e complessa riflessione sul cinema, sullo statuto dell’immagine e, in particolare, dell’immagine-memoria.

Continua la lettura di JOANNA HADJITHOMAS e KHALIL JOREIGE“SI PUÒ FARE!”: RETROSPETTIVA SUL CINEMA HORROR CLASSICO

La celebre battuta pronunciata da Gene Wilder in Frankenstein Junior (1974) di Mel Brooks è stata scelta come titolo per la retrospettiva che il Torino Film Festival 37 ha dedicato al cinema horror classico. Trentasei film che attraversano un periodo di cinquant’anni, dal 1920 al 1971.

Continua la lettura di “SI PUÒ FARE!”: RETROSPETTIVA SUL CINEMA HORROR CLASSICOSOLDATI’S DAY

Article by: Arianna Vietina

Translated by: Giorgia Bellini

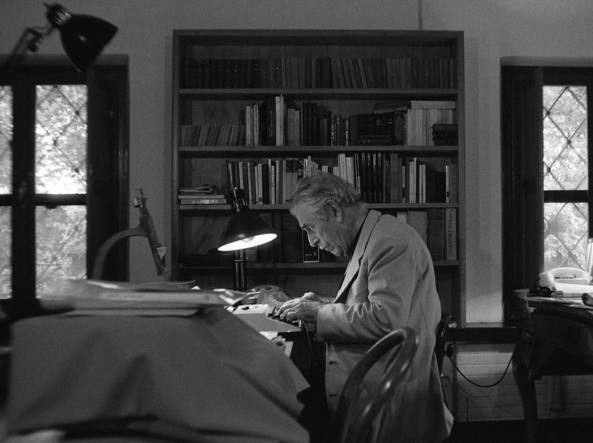

Mario Soldati was an all-round author, a cultured man who has dedicated himself to literature, cinema, television and journalism. He has been the writer and the director of his own life. Born in Turin in 1906, he died in 1999 and, on the twentieth anniversary of his death, we’re talking about him again. Who was Mario Soldati? Why do we keep talking about him? Do we keep on making the same mistake of underestimating him?

SOLDATI’S DAY

Mario Soldati è stato un autore a tutto tondo, un intellettuale che si è dedicato alla letteratura, al cinema, al piccolo schermo, al giornalismo. È stato l’autore di se stesso, scrivendo e dirigendo la propria vita.

Nato nel 1906, è morto nel 1999: quest’anno ricorre dunque il ventennale della morte e si torna a parlare di lui a Torino, la sua città. Chi era Mario Soldati? Perché torniamo a parlarne? Corriamo il rischio di continuare a sottovalutalo ingiustamente?

Retrospettiva di Brian De Palma

La 35° edizione del Torino Film Festival ha reso omaggio, con una retrospettiva quasi completa, al maestro Brian De Palma, uno dei registi amati dalla direttrice del festival Emanuela Martini, la quale lo ha definito così: «De Palma è un mago dello schermo, uno di quei registi ai quali è quasi sempre riuscita la magia di tenere lo spettatore attaccato alla sedia con gli occhi fissi sullo schermo , un maestro di stile, erede di Hitchcock, ma anche di Godard e di Ejzenštein». Continua la lettura di Retrospettiva di Brian De Palma

“Things to Come” (“La vita futura”) di William Cameron Menzies

Nell’immaginaria città anglosassone Everytown è in corso la seconda guerra mondiale: guerra iniziata nel 1940 e che proseguirà fino al 2040. Questa è la ragione per cui i cittadini stessi, nipoti e i bisnipoti, non si ricordano nemmeno i motivi per i quali tale guerra fosse iniziata. Il film Things to Come è stato diretto da William Menzies, uno dei maggiori scenografi della storia del cinema, che crea un gioco visivo tra utopia e distopia.

Continua la lettura di “Things to Come” (“La vita futura”) di William Cameron Menzies