Nella sezione del TFF denominata My Son, My Son, What Ye Have Done (dal titolo di un film di Werner Herzog) sono stati presentati cinque cortometraggi che hanno in comune la tematica dell’amore. Tutti diversi nel modo di raccontare. Mai banali.

Il foglio di Silvia Belotti

Fino dall’alba in via Oberdan a Napoli molte persone scrivono il proprio nome su un foglio attaccato al muro della sede delle Agenzia delle Entrate, necessario per dare ordine alla fila interminabile di coloro che si recano in questo ufficio. Il foglio separa la società (esterna) dalla burocrazia (interna) degli uffici. Tra litigi e riflessioni, tra chi aspetta il suo turno, la macchina da presa riprende quanto avviene con taglio giornalistico tralasciando qualsiasi intento narrativo.

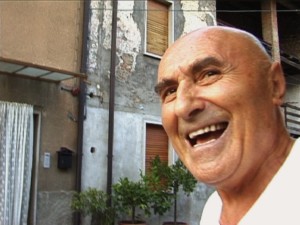

Il suo nome di Pedro Lino

Una carrellata inquadra un muro a secco che sembra interminabile, poi un anziano che cammina a fatica tra i campi. Qua e là qualche pecora. Inquadrature fisse e movimenti lenti scandiscono questo ritratto-intervista di un anziano che vive da solo in campagna dal 1966. Scopriamo la sua vita dalle sue parole e dalla sue fotografie: la gioventù, il servizio militare, la sorella, i suoi tentativi di sposarsi con una donna di cui non ricorda il nome. Tutto è conservato, compresa la Lancia Prisma che non ha mai guidato, come in un museo della memoria. Il vecchio racconta la propria vita senza rimpianti, con parole e gesti molto spontanei.

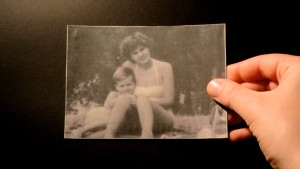

Il dossier di Mari S. di Olivia Molnar

Olivia Molnar ci racconta, nel suo primo cortometraggio, la storia di sua zia Mari attraverso inquadrature fisse di foto e libri e brevi filmati. Mari S., ungherese, vive la controrivoluzione del suo Paese negli anni Cinquanta e fugge a Genova. La sua vita dal 1953 al 1989 è documentata attentamente dai Munka Dossziè, i rapporti stilati da due incaricati dei servizi segreti che Olivia recupera nel 2014 tramite l’Archivio di Stato. Gli anni successivi sono ricostruiti dalla regista per non permettere che tutto venga cancellato dall’Alzhaimer di Mari.

Neuf cordes di Ugo Arsac

La lira di Orfeo aveva nove corde. I primi musicisti furono gli dei. Orfeo fu colui che riuscì ad incantare anche loro con la sua musica. Il mito di Orfeo, che torna dagli inferi senza Euridice, si intreccia a storie di rivoluzione in Ucraina attraverso le opere di due scultori. Il trait d’union tra Orfeo e l’Ucraina è il marmo di Carrara: l’inferno può essere anche bianco. Una fotografia meravigliosa ci guida all’interno di paesaggi suggestivi, con immagini molto contrastate cromaticamente. Denuncia e poesia, disagio e arte, viaggio interiore del protagonista e dello spettatore si mescolano in un’opera prima matura e lirica, scritta, diretta e prodotta dal giovane regista francese.

Scherzo di Fabio Scacchioli e Vincenzo Core

Il secondo movimento della Nona di Beethoven accompagna un pout-pourri di immagini che si susseguono rapide: il mare, i viaggi nello spazio, spezzoni di film hollywoodiani e documentari si muovono insieme alla musica, alle voci, agli applausi in sottofondo in un viaggio surreale, divertente, in un percorso che sale e scende, che si avvicina e si allontana. Il cortometraggio celebra la magia del cinema: nessuna storia, ma uno sfiziosissimo e sapiente montaggio.